It is early 2013, the mist is settling over North-West London. A dear friend of mine and I are on bus route 31 from London’s Camden Town to White City, a bus route I have never been on before. I haven’t lived in London for long, however, hopping on buses heading towards unfamiliar locations has become somewhat of a tradition. When passing through Elgin Avenue and Harrow Road, I suddenly catch a glimpse of an immensely large tower block looming over the surrounding estates.

With its bold veneer, thirty-something floors and separate lift tower, Ernö Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower astounds me in a jolie-laide sort of way. Being brought up in the Swedish, rather small and cobble-stoned city of Lund, where medieval chocolate-box houses are every real estate lover’s ultimate dream, the tower block’s big and bulky, almost intimidating, appearance instantaneously captures my interest. Unbeknownst to me, I would be similarly stunned when wandering through the Alexandra Road Estate near Abbey Road in late 2014.

Later that afternoon, I google search the estate and discover an architectural style I have never heard of before — brutalism. Suddenly, the aspiration of living in a tranquil chocolate-box cottage with period features, or a stylish Victorian townhouse with high ceilings and large bay windows had shifted. I was intrigued, and unsure of whether it was the beauty — or ugliness — of Brutalist architecture that had captivated me. Or perhaps both?

History

Swedish architects Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm’s Villa Göth in Uppsala, Sweden, has long been considered to be the origin of the term Brutalism. In 1950, fellow architect Hans Asplund famously used the term to describe Villa Göth’s relatively plain and blocky design. It was later recognized amongst a group of British architects and was ultimately used in the title of British architectural historian Reyner Banham’s 1966 book “The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?”.

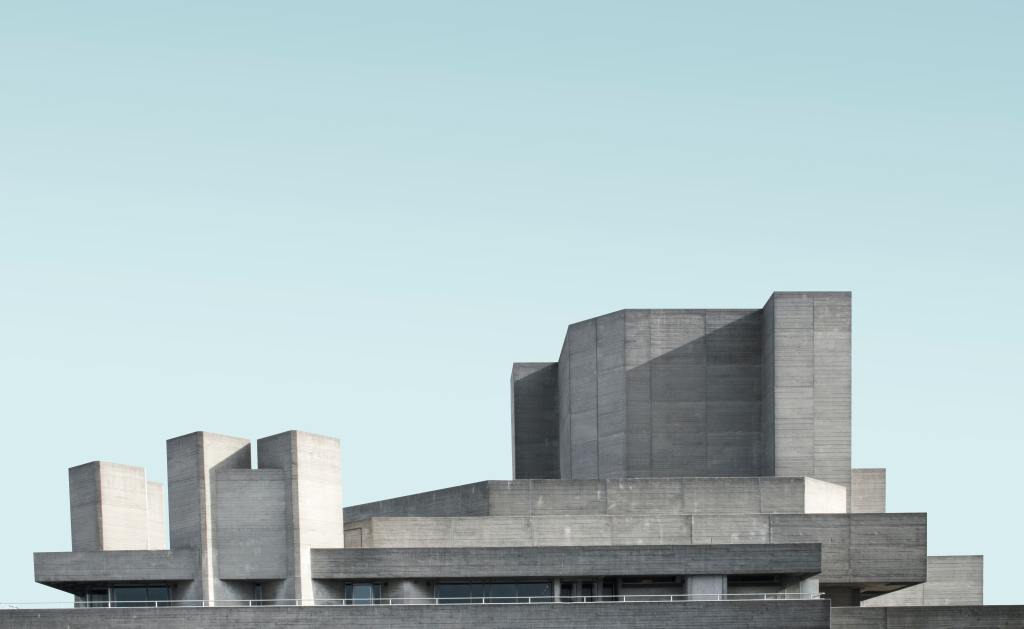

Brutalist design dates back to the 1950’s, with Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier as one of its pioneers. The purpose of many of Le Corbusier’s designs was to improve the living conditions for residents in overcrowded cities. The use of concrete and exposure of rough and unpolished surfaces are the most common features in Brutalist buildings. In the United Kingdom, Brutalism became rather popular in the aftermath of World War II, as deprived groups of the population needed an inexpensive method of constructing social housing, shopping centres and other facilities.

I ask Lukas Novotny, writer and illustrator of newly released “Modern London: An illustrated tour of London’s cityscape from the 1920s to the present day”, if the Brutalist movement was essential. He replies: “Well, it happened, so yes — it was necessary! It didn’t appear overnight; architecture styles are not that different to those in art or fashion, although architects would like you to think otherwise. The new style often starts as an opposition to the prevailing force, in this case ‘soft’ Modernism. At first, it’s used by innovators and a lot of thought is put into its theoretical part. Later, it’s adopted by the mainstream, which usually omits the theory and just uses the visual”.

Concrete and unpolished surfaces — what else? Brutalist buildings are notorious for their functional and effortlessly linear and blocky appearance. Other industrial materials, such as brick, glass or steel, was commonly used in most of its constructions as well. The style thrived from 1950’s to the 1980’s as communities in the United Kingdom, as well as in other European countries, started rebuilding themselves post-World War II. These buildings were never built from high-priced or luxurious supplies, never built to impress the elitists. Perhaps that is why Prince Charles once stated that Brutalist constructions were “piles of concrete”.

The construction of the infamous Trellick Tower had not even been completed before Brutalist architecture was condemned as cold and characterless. Since the 1950’s, many buildings have been demolished, the Tricorn Centre in Portsmouth was one of them. Designed by English architects Rodney Gordon and Owen Luder, the shopping centre and nightclub was purposely designed as an empty canvas, where its occupants and their displays would deliver the colour and liveliness. However, in the 1980’s, the centre was famously voted the third ugliest in the United Kingdom in a poll and despite several attempts to get it listed, The Tricorn Centre was demolished in 2004.

In the 2014 BBC Four documentary “Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry”, English author and film-maker Jonathan Meades explains Brutalism brilliantly: “This modernism was in reaction to the smooth, sleek, elegant work which had preceded it. It didn’t seek to be pretty, it didn’t seek to soothe. We don’t expect films or novels or paintings or sculptures to be pretty so why should we expect buildings to be pretty? There are other qualities we seek. Nightmares are more captivating than sweet dreams, more memorable too. They stick around longer.”

Brutalist London

I have arranged a meeting with Robin Wilson, a lecturer at The Bartlett School of Architecture in Bloomsbury, Central London. We have agreed to meet at the Quaker Friends Meeting Café on Euston Road. Robin has been teaching Architectural History and Theory at the University College London for the past ten years and co-authored the “Brutalist Paris Map” with his colleague Nigel Green in 2017. We are sitting at one of the tables in the bustling Quaker Centre’s corridor space, the unsettling sound of a coffee grinder goes off in the background. Midst lunch-time, the café is extremely busy. Workers are tapping away on their laptops, sipping their soft drinks, teas and coffees.

“Texture and structure, form and function. Brutalism is more than just concrete, it’s a celebration of materials, materials that are used honestly”, Robin explains. He talks with his hands, in a very kind and approachable manner. Whatever question I ask, he answers in a very calmly, and in detail. I explain my interest in the Trellick Tower and the Alexandra Road Estate. He lights up and explains: “The Alexandra Road Estate was the result of the decreasing support of high-rising tower blocks. The residents sought medium density housing with gardens – a sense of community”, he responds.

Throughout our conversation, I learn that Robin himself lives on a Brutalist estate, the Whittington Estate in Archway, famously used the 2018 BBC drama “Bodyguard”. “I very much enjoy the architecture both internally and externally, including the more ‘brut’ aspects of it. Remember though, there are such a range of architectures included under the brutalist nomenclature, and all are very different, with different qualities. As much as I like the brutalist aspects of the Whittington, I also like it because of its modernity in general, and the very carefully thought out domestic design”.

Similarly, to the Alexandra Road Estate, the Whittington is a low-rising estate with plenty of greenery. Designed by British-Hungarian Peter Tabori — a former employee of Brutalist icons Denys Lasdun and Ernö Goldfinger — in the 1970’s, the estate has subsequently become very sought-after. “The community is appreciative of the estate, not just because of the flats themselves, but also because of the large communal public spaces and absence of traffic. Many designers that have flats there, and many long-term council tenants are very settled, some of whose children have stayed on the estate to get a flat of their own. It is a successful community”.

For sightseers that recognize London solely through films and TV, it is easy to believe that it purely consists of six hundred square miles of Mayfair-esque mews and cotton candy-coloured houses. Though London is a stunning city indeed, I do believe the common impression of its prettiness is rather mislaid. Even the most tourist-packed areas; bustling Camden, Fitzrovia’s Tottenham Court Road and West End have several works of Brutalism worth discovering.

When asking Lukas Novotny for recommendations, he suggests: “Apart from the obvious spots like Barbican or Southbank, I would recommend just walking or cycling and finding things by chance. London has arguably the best Brutalist architecture in the world and it’s scattered all over the place”. Jacket on and rucksack packed, I start off my excursion, eager to explore Brutalist London. First off, Balfron Tower. At Bethnal Green’s Bonner Street, I hop on the D6 towards Crossharbour. It is a crisp and sunlit December morning; Christmas lights have gone up along Roman Road. Outside the Post Office, locals are queuing up to send off Christmas cards and presents to their loved ones. It is a gorgeous day.

The bus passes by Canary Wharf, London’s skyscraper-filled financial district. The glass facades of the high-rising towers are glistening in the sun and the strong contrast to the neighbouring council housing estates is self-evident. Approaching the Brownfield Estate and the Balfron Tower, I spot Goldfinger’s other work — Carradale House. With similar designs and exteriors, the two buildings complement each other cleverly. Whilst Balfron Tower stands tall, Carradale House lies long. The concrete surfaces of both buildings shift in sooty greys and sandy browns. Although their shells might appear dark, generously large windows gives off the impression of a bright interior. Most of Balfron Tower is sadly covered in scaffolding, however, recognizing the similarity to its sibling Trellick Tower, I am reminded of that bus journey in 2013.

Jumping on a Docklands Light Railway train, I head towards Archway and the Whittington Estate. Slowly moving past the rooftops of Poplar, Westferry and Shadwell, I admire the scenery. A woman is hanging out her laundry and school children are joyfully playing on the basketball courts. Half an hour or so later, I arrive in Archway, North London, and I start walking towards the Whittington Estate. I pass a young man playing Christmas melodies on the accordion. As I am getting closer to the estate, I am surprised of the village-like atmosphere; plenty of families, Victorian houses and a traditional English pub at every corner. Turning onto Dartmouth Park Hill, the Whittington Estate suddenly emerges. Being rather low-rise, with a soft beige exterior and plant-filled balconies, it blends into its surroundings attractively.

In contrast to the high-rising Balfron Tower, the appearance of the Whittington Estate reminds me of Neave Brown’s Alexandra Road. It is warm, welcoming and has a sense of community. Whatever the shape or size of these concrete wonders, each of them is as beautiful as the next. Nonetheless, Brutalism still is a peculiar matter. As Lukas Novotny explains: “Brutalism is one of those topics you don’t want to mention over a family dinner. Your uncle might live on a 1970’s estate, which council neglected for decades and where they dropped off the worst social cases. He couldn’t care less about the names of the architects, their original vision or any of that. That uncle would have an argument with your high-heeled brother, who lives in a Victorian terraced house and buys overpriced coffee table books about Brutalism”.

So, is Brutalism awfully ugly, or exceedingly beautiful? That is entirely up to you. Nevertheless, do all things need to be beautiful in order to be thought-provoking? After all, Brutalism was somewhat of a saviour in post-World War II Britain, when families were struggling to find housing they could afford, if any housing at all. And Brutalism was more than simple and inexpensive supplies, it had thought, meaning and imagination behind it. Brutalist designers used materials honestly, kept them rough and unpolished, something that rarely happens in this contemporary day and age. Thus, if you ever find yourself having nothing to do in London, hop on a bus or train towards an unknown location. You might discover a building or street you never thought you would.

Photo by Simone Hutsch on Unsplash

Leave a comment